From Reagan to Trump: Lessons for Responsible Reporting After Violence and Crisis

by Mariano Avila

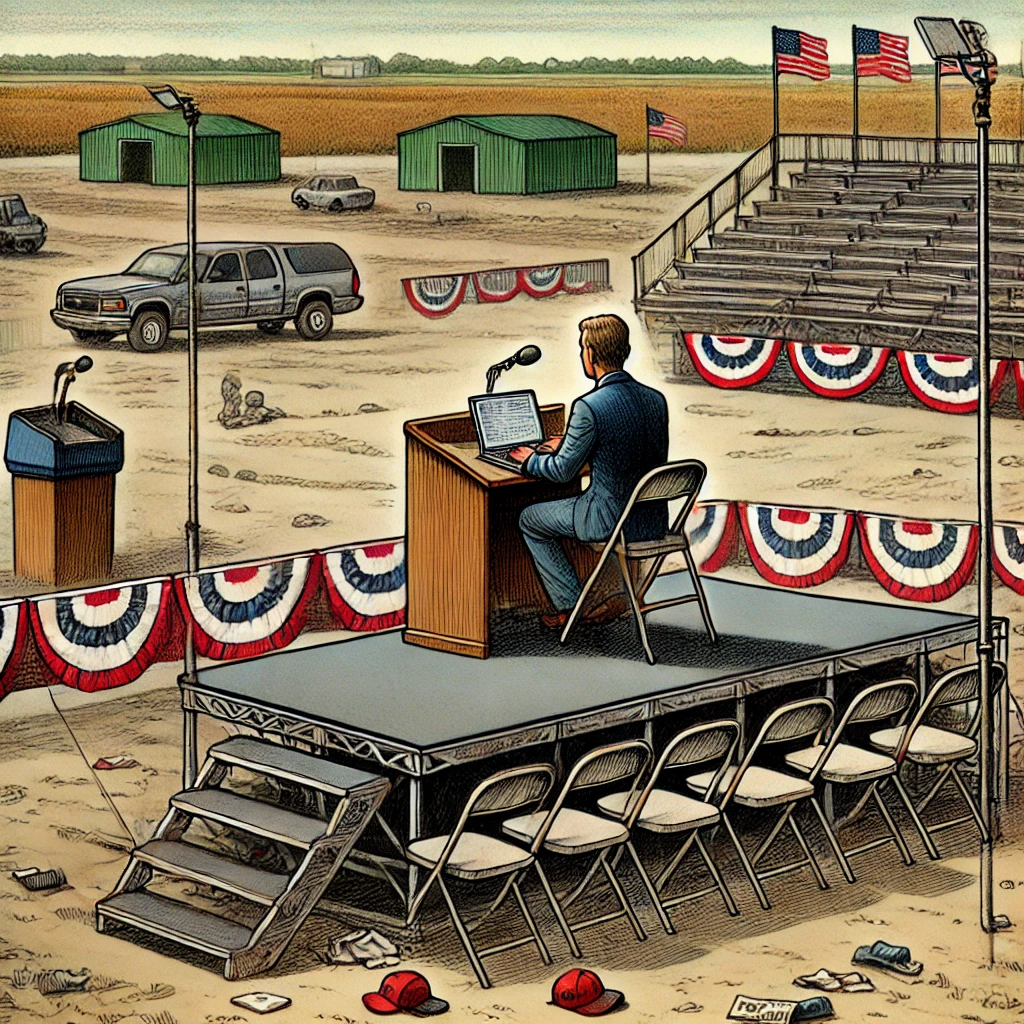

Illustration created by Mariano Avila using DALL-E text to image generator

What happened on Saturday is a terrifying turn in American history and a sad day for our democracy. Regardless of what party we support or which candidate wins, the impact of this attempt on Donald Trump’s life will be felt for years to come. And while the news cycle has moved onto JV Vance as Trump’s pick for VP, it will be increasingly important to use those instincts that made us journalists and to remember the many, hard-won lessons from our industry’s failures and triumphs going as far back as the attempt on Reagan and as currently as the aftermath on the attempt this past weekend.

Here’s my call to action as we strive to be factual, fair, and first. Let’s do just that—but let’s do it better each time.

I. Verify: Don’t Rush to Be The First to Get It Wrong

Make sure your sources are all verified and first-hand. Don’t just follow what other news outlets report.

When President Ronald Reagan was shot on March 30, 1981, journalist Louise Schiavone covered it for AP Radio. She recounted for NPR how she rushed to George Washington University Hospital where the Acting White House Press Secretary, Larry Speaks, told reporters that both President Reagan and Press Secretary, James Brady, who was shot in the head, were alive and receiving treatment. But CBS was saying that Brady was dead, so Schiavone’s editors asked her for a death certificate. She stuck to what she knew and AP didn’t report Brady’s death. To be fair, Brady eventually succumbed to his wounds and in 2014 his death was ruled a homicide. But CBS jumped the gun by 33 years.

At this point we have a limited number of pertinent facts and yet we have an equal number of false statements. One gaining traction online: The FBI identified the shooter as Thomas Matthew Crooks. But X (formerly Twitter) is aflutter with theories that the shooter is either Maxwell Yearick or Kennon Hooper.

This is not a minor detail and it puts both Yearick and Hooper in danger, if they are indeed real people. And that leads to the next matter to keep an eye out for— the creation of enemies.

II. Enemies—the main ingredient of propaganda

When my father-in-law looked up from his phone during dinner and said “this is not a hoax, someone just shot at Donald Trump,” showing us the news clip on his phone, my first thought was, please don’t let the shooter be a racial or religious minority. This may seem scandalous to some, but it’s a familiar fear for minorities whose entire people group has been deemed an enemy over the actions of a violent individual.

Ask yourself, if the shooter had been Latino, how much would that have fueled anti-immigrant, anti-refugee rhetoric around the country and along the border. If the shooter had been a Muslim or Middle-Eastern person, how much worse would anti-Muslim/anti-Arab actions have become.

For better or worse, Crooks was a white man and seemingly Republican, so scapegoating his “ethnic” group is one less thing to worry about—he gets to be a lone wolf, an individual with mental illness, or whatever they find on him, but no people group will get targeted in association with him.

Casting blame on political rivals

Unfortunately, shifting the blame from the shooter to political rivals or the government is well underway:

Congressman Mike Collins (R-GA) tweeted that “Joe sent these orders.”

Valentina Gomez, running in Missouri for Secretary of State, posted a video on Instagram saying that Trump’s security team is compromised.

The attempts to paint Democrats as responsible due to their rhetoric is already becoming old news. It seems there is an agreement to turn down the temperature on campaign rhetoric from both parties. We will see how it changes and if both parties stick to it, but as the calls for moderating language continue, our job is to use language to keep the story factual and within an appropriate scope and tone. How? Glad you asked.

III. Sensationalizing: It’s already bleeding, don’t make it hemorrhage

The adage, “if it bleeds it leads,” with its emphasis on violent crime in many newsrooms is desensitizing the public, and potentially even influencing “copycats.” This despite the fact that there has been a 59% decline in violent crime in America in the past 30 years.

So how do we avoid sensationalizing an already staggering event like this attempt:

Don’t show graphic Content: It’s perhaps the hallmark of yellow journalism to be gory, but what value does it add to the public when we show graphic pictures of the shooter’s dead body? And yet, social media is flooded with them right now, especially X.

Avoid dramatic language: keep headlines and posts, or any other part of your report, factual and measured. Compare these two headlines from the NYT:

Shooting at Trump Rally Comes at Volatile Time in American History

An Assassination Attempt that Seems Likely to Tear America Further Apart

Don’t give speculation airtime: Sometimes it comes from a prominent politician implying conspiracy, but in the worst cases, it’s the journalist being careless.

IV. Newspeak: new language is coming, be ready to question it when it hurts the public.

The journalistic challenge with events like the assassination attempt, is that it will be used to serve different political agendas, leading to new language developed to spin politically expedient narratives.

In the aftermath of 9-11, terms like Axis of Evil or The War on Terror were used to start a war on a nation that had nothing to do with the attacks, because we were told there were WMDs (weapons of mass destruction) in Iraq. There was also language developed to silence dissent or critique of the war: “don’t you support the troops?” Between 100k and 1 million Iraqi deaths later, depending on who you believe, those weapons were proven to not exist.

Going back to the vilification of whole categories of people, and so it’s clear both parties use these tactics, let’s not forget Superpredators, coined by academics, disseminated by media, and ultimately promoted on the highest platform by then First Lady, Hillary Clinton. This was the idea that minors, primarily Black kids, from poor neighborhoods and with prior convictions would grow up to be the worst threat to American society. This turned into a nationwide campaign of overpolicing and mass-incarceration that is still affecting communities of color.

Newspeak is a term from George Orwell’s novel 1984, referencing “official” language meant to limit the public’s capacity to discern reality. Stay vigilant against language that targets people gorups, promotes violence, or punishes critical thought without addressing arguments against it.

V. Transparency: The antidote to conspiracy

It’s ok to say you don’t know or that information that others are reporting is not verified. I think it’s admirable when the pressure to keep up with other stations doesn’t lead to reporting inaccurate information. Your audience will trust you more if you don’t have the info first but you seem to consistently get it right.

A notable example was the Boston bombing. Several news outlets stated that the suspects had been arrested when they weren’t. But one of the most dangerous instances was the cover of The New York Post who published a photo of two high-school runners from Boston with the headline “Bag Men” while the search for the suspects was still underway. The Washington Post has an account of it. Among those that held out reporting on the identity and the capture of the suspects, was NPR. I couldn’t really find a record of it because, well, they only reported once they knew, but that’s the point I guess.

Another example of how to address misinformation is to call it out directly. Keeping with the Boston Bombing, ABC dedicated an article precisely to what it called dead-end rumors.

Press Addresses Trump Attempt Rumor-mill

Here are a few folks doing just that, calling out the rumors directly. There are at least half a dozen, which warms my heart to see, but I’ll just include three.

1. PBS: Fact-checking the wild conspiracy theories related to the attempted Trump assassination

2. Reuters: We fact-checked some of the rumors spreading online about the Trump assassination attempt

3. CBS: Missinformation and conspiracy theories swirl in the wake of Trump assassination attempt

Above all, regarding transparency, be quick, clear, give attribution and context when you do make a mistake. In fact, promote it. In this environment, people will forgive the mistake and respect the integrity. Conversely, it’s easy to catch mistakes these days and we lose a lot of credibility when we don’t own up to our mistakes as soon as we find them.

Conclusion

The rhetorical temperature may come down, but it’s doubtful. Meanwhile, faster fact-checking is becoming more prevalent—brilliant. However, the effects of events like these can still lead to new conspiracies and the vilification of vulnerable groups. Stay alert and ahead of those spinning facts to weave narratives that divide, hurt, or confuse the electorate. You’ve got this!